THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

POLITICS

U.S. Nears Settlement With Sudan Over 1998 Terror Bombings

Plan is part of U.S. efforts to support the civilian-led transitional government in Sudan

By

Jess Bravin and

Jessica Donati

Updated May 19, 2020 11:05 pm ET

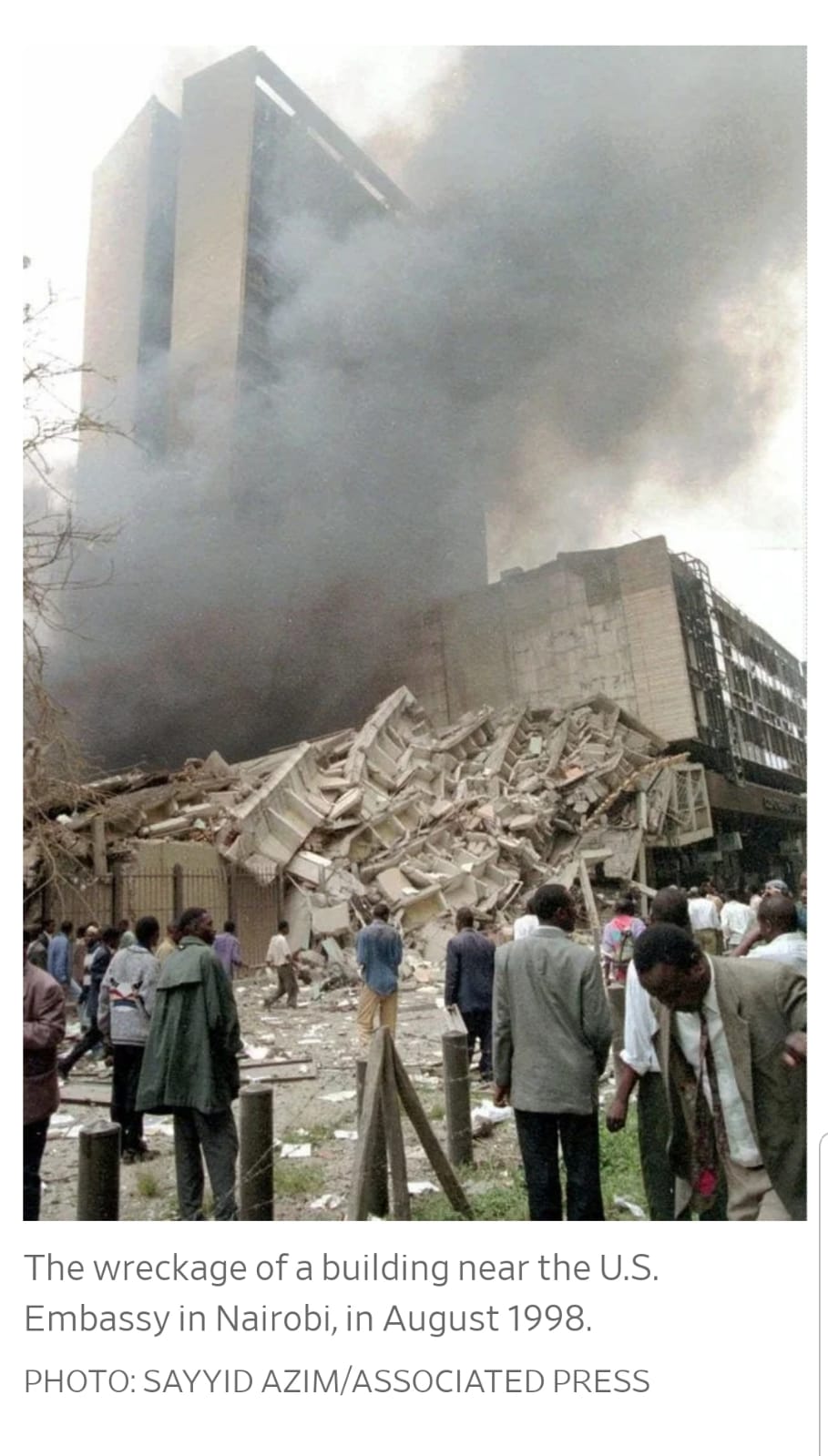

WASHINGTON—The Trump administration is nearing a deal with Sudan to resolve claims over al Qaeda’s 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Africa, helping clear the way to remove Khartoum’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The plan is part of U.S. efforts to support the civilian-led transitional government in Sudan, whose armed forces last year ousted President Omar al-Bashir, a military dictator who seized power in 1989. Earlier this year, Sudan settled terrorism-related claims from the 2000 al Qaeda suicide bombing of the USS Cole during its call at Aden, Yemen, which the Bashir regime allegedly had assisted.

“Following extensive negotiations, we believe that we have reached a common understanding with Sudan on the contours of a future bilateral claims agreement” over the embassy bombings, a State Department official said Tuesday. Victims would receive more than $300 million altogether, a congressional aide said.

The 1998 attacks in Kenya and Tanzania killed hundreds and injured thousands, and various groups of victims are represented by different legal teams. Twelve Americans were killed.

On Monday, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected Sudan’s bid to delete $4.3 billion in punitive damages from a $10.2 billion verdict victims won against Khartoum in federal court.

Still, the odds of collecting on that judgment are steep, making a U.S.-negotiated settlement the most plausible way that victims would see any compensation. Some of the plaintiffs complain that the State Department’s plan gives short shrift to victims who were foreign nationals, because their deaths would be worth about 10% of an American’s.

According to plaintiffs’ lawyers, the plan would pay $10 million for each U.S. government employee who was an American national when killed, but only $800,000 for each government employee who was a foreign national. Injuries for the U.S. nationals would be worth from $3 million to $10 million, compared with $400,000 for foreign nationals.

“The value of a life is not dependent on where a person is born,” Doreen Oport, who worked for the embassy in Nairobi and now lives in Texas, said in a statement the lawyers released. “The State Department is betraying U.S. victims and the American principles of equality and rule of law that the Sudan-back terrorists found so threatening 20 years ago.”

Those complaints have won sympathy from some lawmakers, including Rep. Bennie Thompson (D., Miss.).

“I gather that there are some Gulf States who may be willing to put up the settlement money, likely to facilitate future business in Sudan,” Mr. Thompson said in an April letter to House committee chairmen.

But “a two-tiered system that blatantly disrespects the service of the Kenyans and Tanzanians who were working in our Embassies as U.S. Government employees would be wrong and inconsistent with the law,” he wrote. “In fact, many of these so-called ‘foreign service nationals’ have since moved to America and become citizens.”

The State Department official defended the plan.

“While no amount of money can compensate for the loss of life and injuries that were suffered in the attacks on our Embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, the agreement under discussion would secure significant compensation for both U.S. national and non-U.S. national victims of those attacks,” the official said.

The official said Washington had gone out of its way to secure at least some compensation for non-U.S. nationals.

“This has been a high priority for the U.S. government, given that these foreign nationals were our employees and contractors. Sudan’s commitment to provide meaningful compensation for non-U.S. nationals is of an unprecedented nature,” the official said.

A congressional aide said the State Department’s plan may be the only opportunity for victims to recover compensation from the impoverished East African nation.

“The transitional government is in a very tenuous position,” the aide said, and faced a domestic backlash when it agreed to pay $30 million to the families of 17 U.S. sailors killed in the Cole bombing rather than address local needs. “There’s a very small window of opportunity for the victims to get anything.”

The State Department official said the settlement would resolve all claims by U.S. nationals. The U.S. didn’t have power to set aside litigation by foreign nationals, the official said.

Still, Khartoum has reasons to restore its position within the international community. If Sudan gets off the State Department’s terrorism-sponsor list, leaving only Iran, North Korea and Syria with that designation, it could gain access to international markets and restructure debts accumulated over three decades of rule under the Bashir regime.

The U.S. also has reasons for restoring ties. It stands to gain an opportunity to recalibrate geopolitics in a strategic region of northeast Africa, along the important Red Sea waterway. Sudan shares borders with seven other nations, including some that are grappling with militant groups, another factor that makes it a strategic ally for the U.S. in the region.

Sudan’s Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok, told The Wall Street Journal in a December interview that the country could allow the U.S. to set up a counterterrorism operation in Sudan, similar to the model the U.S. uses in the Sahel, where it conducts joint operations with local forces in places like Mali and Niger.

Mr. Hamdok’s government has already moved to recalibrate global ties with U.S. allies, forging closer relations with Israel, a move that was praised by Mr. Pompeo earlier this year.

The State Department declined to say whether the settlement was a final step to getting removed from the list, or what else Sudan needs to do to succeed. In recent months, U.S. officials had begun to express frustration with the slow pace of reforms, including delays forming a transitional assembly and appointing civilian governors.

In March, Mr. Hamdok survived an assassination attempt on his convoy. The little-known Sudanese Islamic Youth Movement, also known as Sudanese Taliban, claimed responsibility for the attack, calling him a “U.S. agent.” The incident raised fears that disgruntled groups loyal to Mr. Bashir, an Islamist, may dent the country’s democratic transition.

The Bashir regime’s legacy goes beyond its support of al Qaeda. Mr. Bashir’s forces allegedly committed atrocities in the nation’s Darfur region, which prompted the International Criminal Court in 2009 to charge him with war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. Sudan’s transitional government said in February it would surrender Mr. Bashir to stand trial at the ICC, but it’s unclear when that might occur.